This article was originally published in The Kathmandu Post, 12 June J 2020

The Limbus, an indigenous people from Nepal’s eastern hills, have interesting and unique food traditions. Wild edible lichen, known as yangben, is the community’s signature speciality. Limbus cook yangben with meat, especially pork, to make a variety of dishes. And one of the most loved delicacies is yangben-faksa, pork with lichen. Another popular dish is blood sausage, known as sargemba or sargyangma, which is made by adding lichen to minced meat or innards.

Yangben doesn’t have any flavour or aroma on its own but when cooked with fatty pork, it absorbs the fat and lends a delicious earthy flavour to the dish. Pork and yangben marry well together.

Because of the yangben’s popularity, neighbouring Rai and other communities have also adopted yangben in their food culture. But from where and how did the lichen become part of traditional Limbu food? Let’s find out.

As with the kinema (fermented soybeans) and alcohol drinking, the history of lichen consumption in Nepal probably has its origins in current southern China’s Yunnan region. Limbu’s ancestors came to Nepal’s eastern hills from Yunnan via Northern Burma and Assam, according to historians. According to the book ‘Kirat history and Culture’, written by Imanshing Chemjong, the Limbus came to eastern Nepal around the seventh century and joined a related group called Kirats who came to the region much earlier.

Lichen is considered ancient food in Yunnan, and in Nepal only the Limbus have traditionally consumed lichen even though it’s widely available across the country’s hills and mountains. Based on this observation, it is only plausible that Limbus might have brought the practice of eating lichen from the Yunnan region.

Here’s another example that supports the claim that the practice of eating lichen in Nepal might have come from the north-east: In 1871, the British Medical Officer John Anderson encountered lichen in a local market of Northern Burma, next to Yunnan, during his expedition from Calcutta to Western Yunnan. ‘A dried, almost black lichen,’ he reported, ‘is sold commonly as an article of food, and mushrooms are much run after.’

People in many parts of the world—Northern Europe, Siberia, North America, Central Asia, and South-East Asia—also consume lichen as food. In India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, people use a lichen known as kalpasi or patthar ka phool to flavour biryani and meat stews.

There’s another hypothesis that as with many other wild vegetables, the practice of eating lichen might have come from humans’ survival instinct. People had to make use of whatever ingredients grew around them.

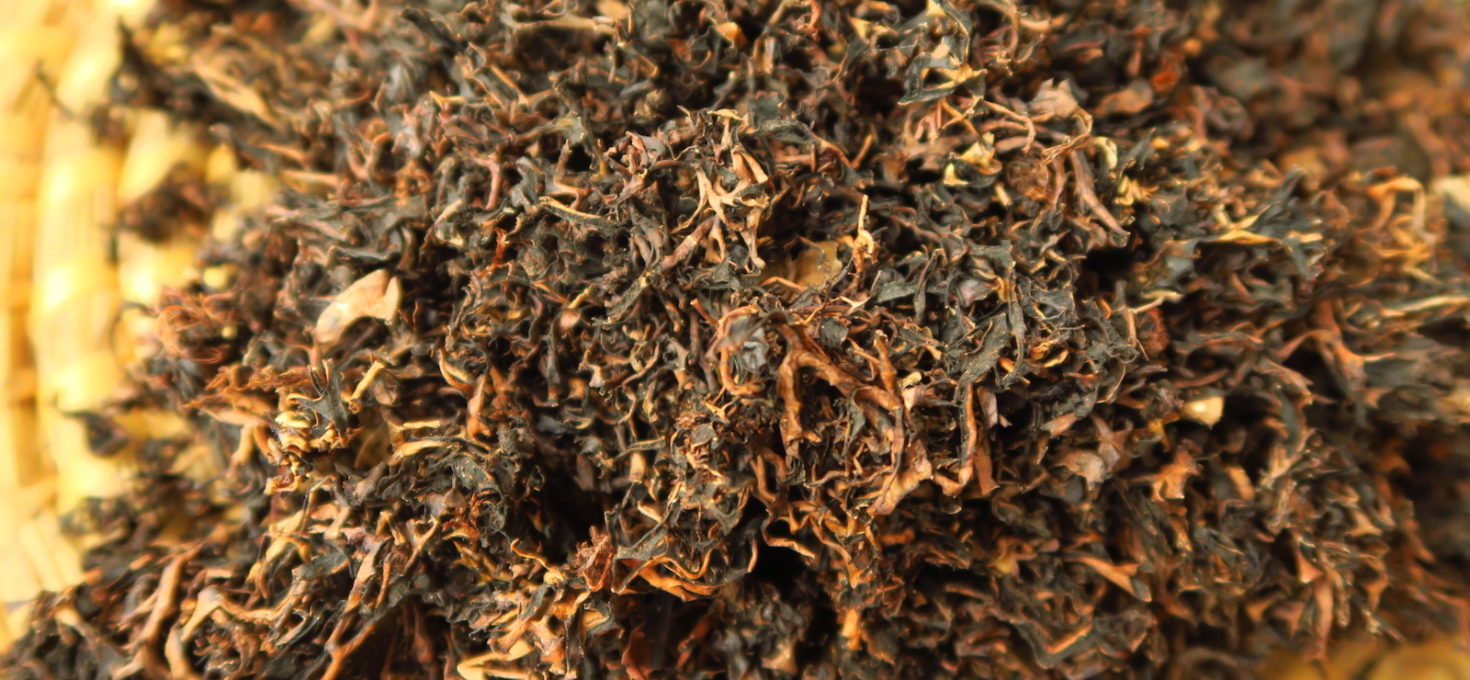

Lichen is a composite organism made up of symbiotic relations of different species of algae, cyanobacteria, and fungi. Limbu and Rai communities consume three lichen species: Everniastrum cirrhatum, Everniastrum nepalense, and Parmotrema cetratum. These filamentous or small leaf-like lichens grow on old chestnut, rhododendron and alder trees.

The process of making yangben is easy. It starts with foraging, then the collected yangben is boiled in water with firewood ash for a few hours. When boiled with ash, yangben turns from light greenish-white to dark-brown. Alkaline ash is used because it removes the lichen’s toxicity, reduces bitterness and makes it tender. There are a few other Nepali communities that also use alkali: Chepangs use firewood ash to eliminate the toxicity and bitterness of wild tubers, and in Mustang, people use naturally found alkaline salt to tenderize dried greens.

Anyway, back to the yangben. After the yangben turns dark-brown, it is then washed with cold water several times until the water runs clean, then the yangben is sun-dried and stored for later use.

In Nepal, people also use lichens to make dyes and for ritual and medicinal purposes. However, the availability of the traditional lichen is declining, says Shyam Sunuwar, owner of a Sabi-Siwani Sekuwa Ghar in Talchikhel, Lalitpur. He sources yangben from Panchthar and Ramechhap, and processes and sells it in his restaurant.

“In the past, only Limbus used to eat yangben,” he says. “But now other communities have started consuming it, and that has led to overharvesting.” There are others who believe that the dust from vehicles that ply the roads built through rural forests have also barred the lichen from flourishing.

This just adds to the fact that the yangben is a prized delicacy among the Limbus. Traditionally, they have been used to gift it to relatives as a koseli. It is a most sought-out item by Limbu and Rai communities living abroad. Outside the eastern hills, yangben is only available in areas with a large diaspora of Limbu-Rai communities such as Itahari and Dharan. In Kathmandu valley, you can find yangben in the Talchikhel-Nakhipot area, in pork shops and groceries run by Limbus.

As said earlier, yangben is almost always cooked with meat and innards of local black pig, which is popularly known outside the eastern region as Dharane kalo sungur. Limbus and Kirats revere this indigenous variety of pig meat and the meat is even offered to their ancestral deities. No festival or special occasion is complete without it.

“Yangben has high-fibre content and doesn’t easily digest, and this helps in reducing the pork’s fat absorption in the body,” says food technologist Huma Bokkhim. “That’s probably one of the reasons why lichen is cooked with pork. In terms of nutrition, it has many minerals,” she adds.

Limbus usually prepare yangben during the festivals of Chasok Tongnam, Sisekpa Tongnam, Kokphewa Tongnam, Dashain and Tihar. “Yangben gives us Limbus our cultural identity,” says anthropologist Dambar Chemjong.

Yangben-faksa, a dish made from pork (including a generous layer of fat and skin), pig’s blood, and lichen, is one of the beloved Limbu delicacies. Fak-sa in the Limbu language means pig’s meat. Sa or sya in many languages in Nepal means meat. Yangben-faksa can be eaten with rice and selroti, and pairs well with tongba or thi (raksi)—a local alcohol of the Limbus.

Below is the recipe of yangben-faksa:

Ingredients:

- 1 kg local black pig’s meat (kalo sungur ko masu), cut into bite-sized pieces

- A fistful of yangben

- 1 cup pig’s blood

- 5-6 garlic cloves

- 1 thumb-size slice of ginger

- 1 teaspoon cumin seeds

- 1 teaspoon coriander seeds

- 1-2 green or dried red chillies

- 1 teaspoon turmeric powder

- Salt to taste

Directions:

- First, make a spice paste by grinding together garlic, ginger, cumin seed, coriander seed and chilies.

- Soak a fistful of yangben in hot water for about five minutes. Drain the soaked yangben, and add a cup of pig blood, half of the spice paste, and sprinkle some salt. Mix them together.

- Heat one or two tablespoons of vegetable oil in a karai or cooking pan over medium-high heat. Add pork pieces with fatty skin and then turmeric powder. Cook until the fat melts and the meat browns lightly, until the meat is almost cooked. Add salt and the remaining spice paste, and cook for a few more minutes.

- Finally, add the yangben-pig blood mixture. Then mix and cook with the lid on, stirring occasionally until the meat is fully cooked. The blood will help to keep the curry moist; it also imparts a rich earthy creamy flavour to the curry.